The Logic Behind the Effort and Added Cost of Passive House

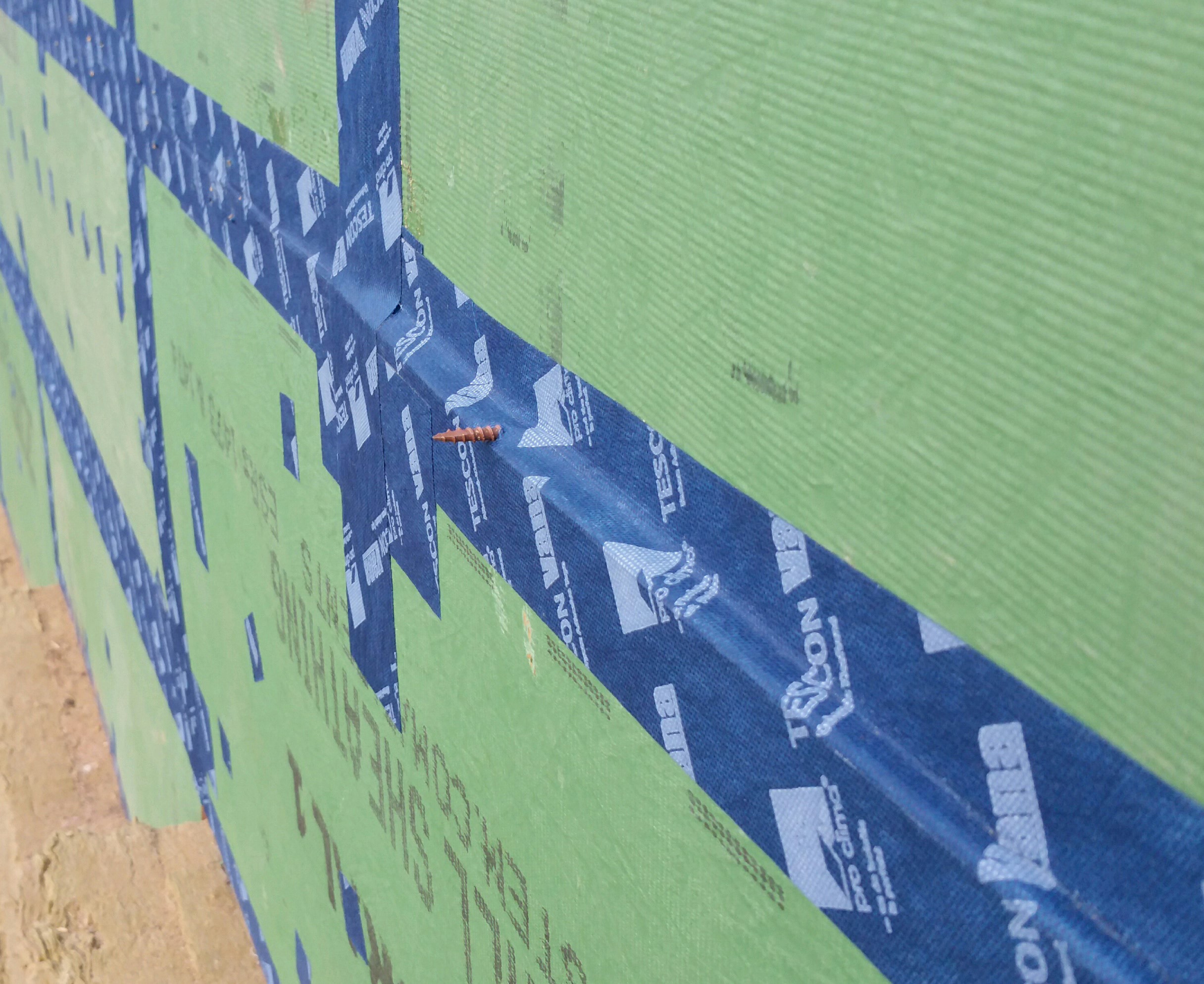

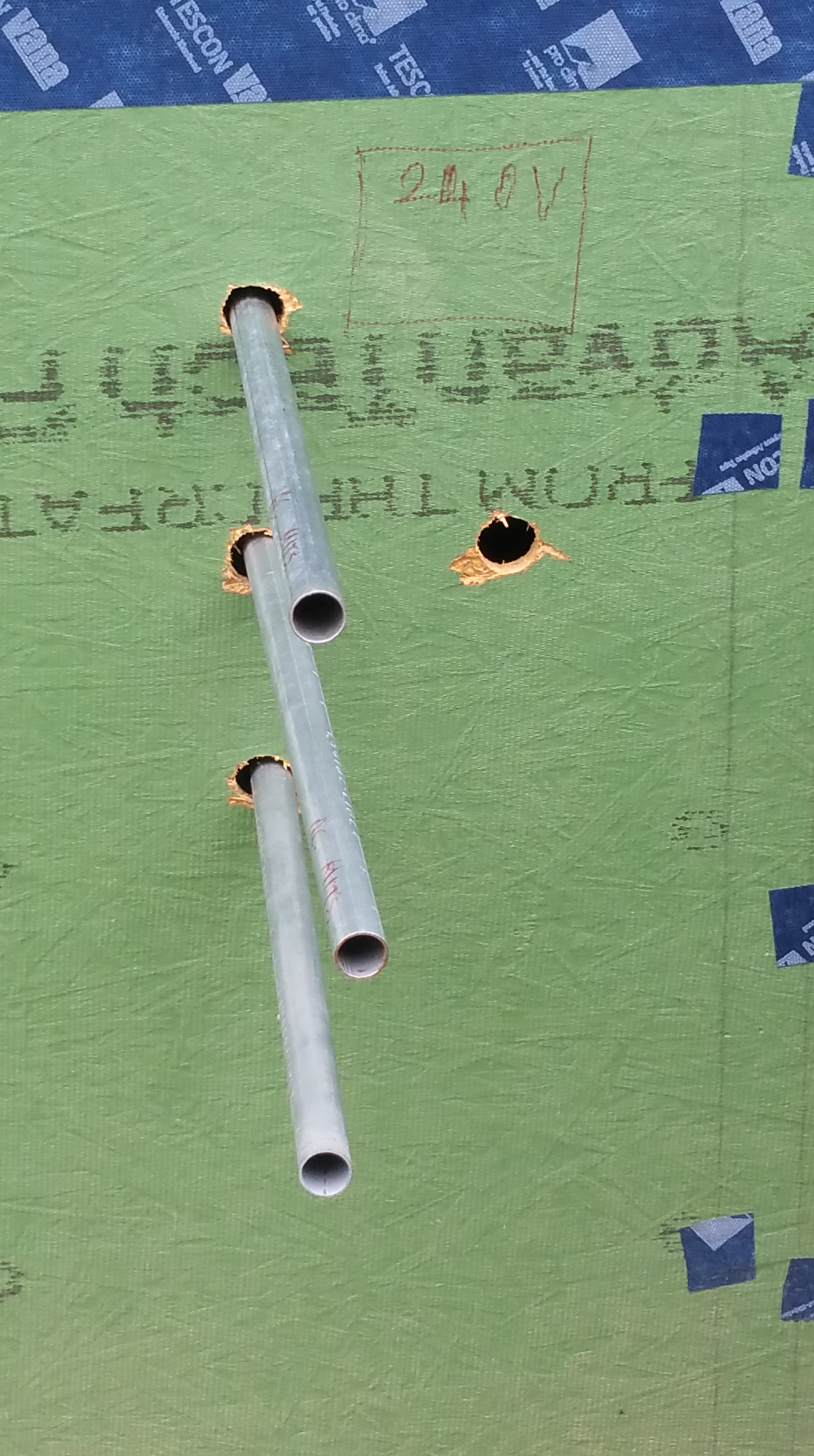

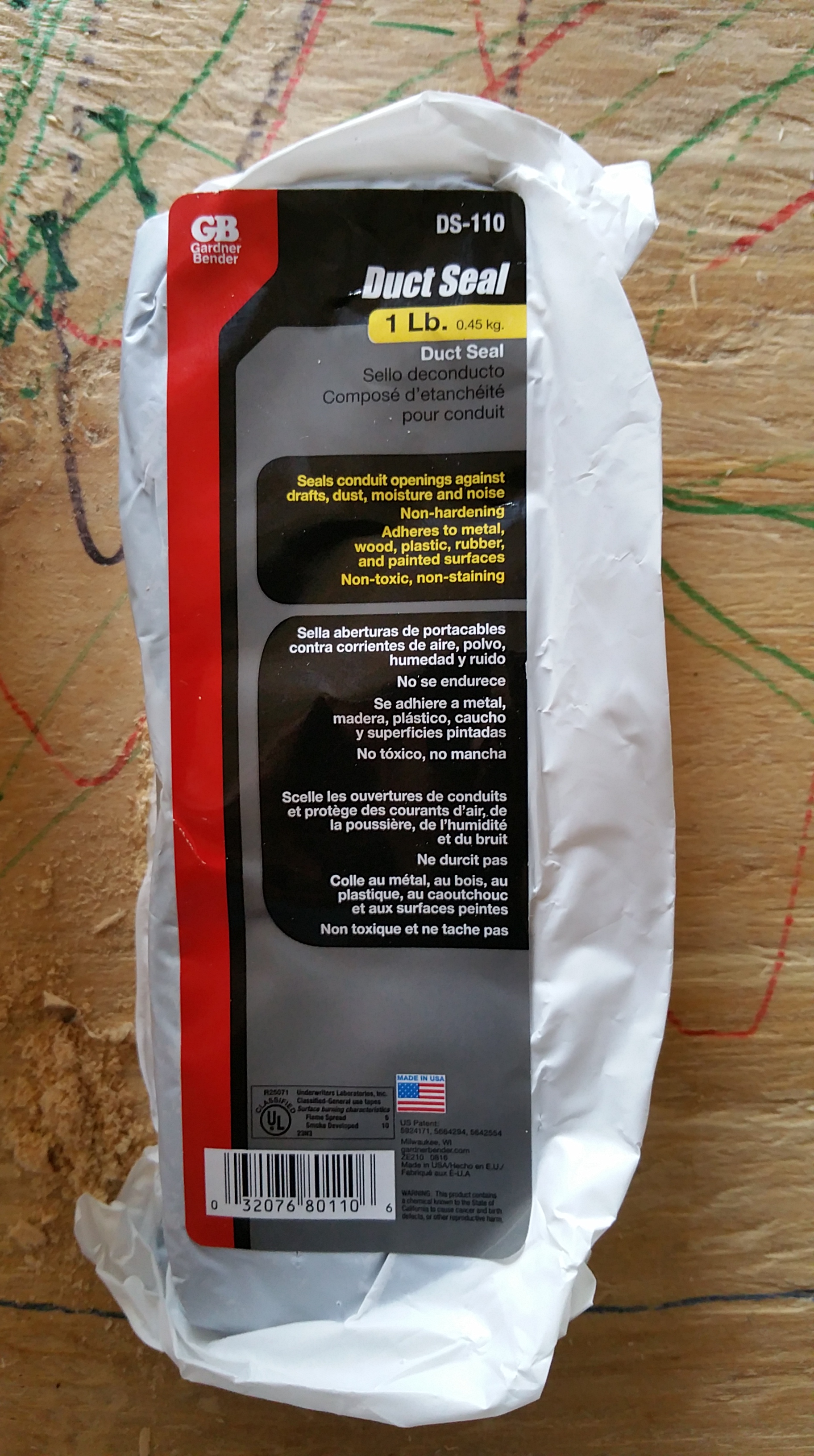

Passive House, as a building strategy, requires meticulous air sealing, along with ample amounts of insulation, carefully placed to eliminate or reduce the impact of thermal bridges through the building envelope. Once the air barrier of the building has been established, it requires mechanical ventilation to meet IAQ needs, along with high performance windows and doors to avoid undermining all of the air sealing and insulation.

All of these elements together, if successfully managed and implemented, should achieve a building that requires significantly less energy to operate and maintain at comfortable temperatures than any conventionally built structure of similar size and shape.

With a ‘conservation first’ approach (i.e., extensive air sealing and insulation), the goal is to reduce total heating and cooling demand as much as reasonably possible (while maximizing occupant comfort), with the possibility of adding renewables like solar or wind as mostly an afterthought to further reduce, or eliminate entirely, the remaining energy demand of the structure. It also typically means going all electric, so in our case it meant no natural gas (the normal fuel source in our area for a furnace and a hot water tank).

A Passive House structure, by design, should use significantly less energy than any conventionally built counterpart of similar size and shape. This includes lighting (normally assumes only LED fixtures will be used) and other plug-in loads (e.g., Energy Star appliances), as well as hot water (typically a heat pump hot water tank, or a newer product like Sanco or Chiltrix).

Unfortunately, these loads are relatively ‘baked-in’, even for an existing, conventionally built home. For instance, a hundred year old home could switch all of their light fixtures to LED bulbs, replace old appliances with new Energy Star rated models, and change out a gas-fired or a conventional electric hot water tank to a high-efficiency heat pump model. In effect, they’d have pretty much the same reduction in energy use as a brand new certified Passive House of similar size and layout for these particular sources of energy demand. As a result, the real opportunities for driving down energy use in a Passive House are in the heating and cooling loads (mainly due, of course, to the extensive air sealing and insulation levels).

Although there has been some moving of the goal posts as the Passive House programs have evolved over time, they remain challenging targets to meet.

Here are the current PHI requirements: Passive House Checklist

In the case of PHIUS, the requirements have gone through several iterations, for instance, PHIUS+ 2015, PHIUS+ 2018, and most recently a fairly dramatic change to a prescriptive track to seek certification with far less onerous levels of paperwork and data collection required.

Overall, regardless of which model is pursued, PHI or PHIUS, the intent is to dramatically reduce the overall energy use of buildings by emphasizing the importance of air sealing, insulating to levels that exceed current code requirements (in most cases), along with quantifying things like thermal bridges, heating and cooling demand, and peak heating and cooling loads. The issue of energy demand or energy use is further complicated by the distinction made between Primary/Source and Site Energy.

Additionally, there’s been a growing consensus regarding the need to incorporate renewables in these building strategies, both in terms of financial feasibility and in terms of further reducing (or even canceling out altogether) net energy demand. And while it’s true that Net Zero is fairly straightforward to achieve (assuming needlessly large PV arrays are not utilized as a short-cut), it does require a commitment to meticulous air sealing and quantities of insulation that, along with the in-depth energy modeling, unavoidably add cost to any construction budget.

The opportunity for significant energy reduction also correlates with the size of the project. Because of form factor ratios, the larger the project (assuming a compact form is mostly maintained) the more energy a structure stands to conserve. This is why larger institutional, multi-family projects, or corporate-sized projects stand to be the biggest winners when it comes to the purported benefits associated with Passive House energy conservation.

If executed properly, low energy demand will mean considerable financial savings. These savings are cumulative, year after year, rather than just a one-off initial price break, with the added potential to increase should energy costs increase.

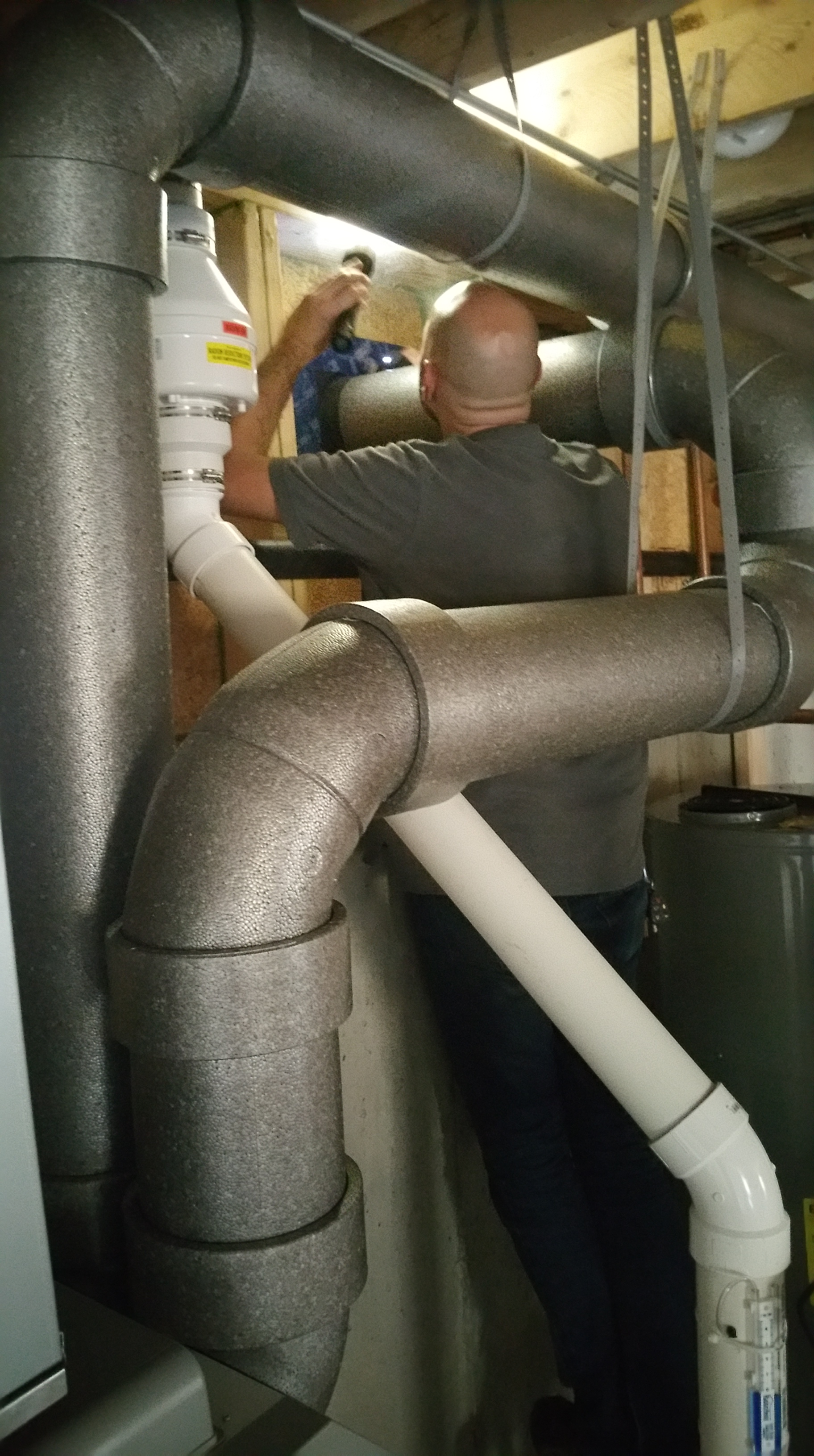

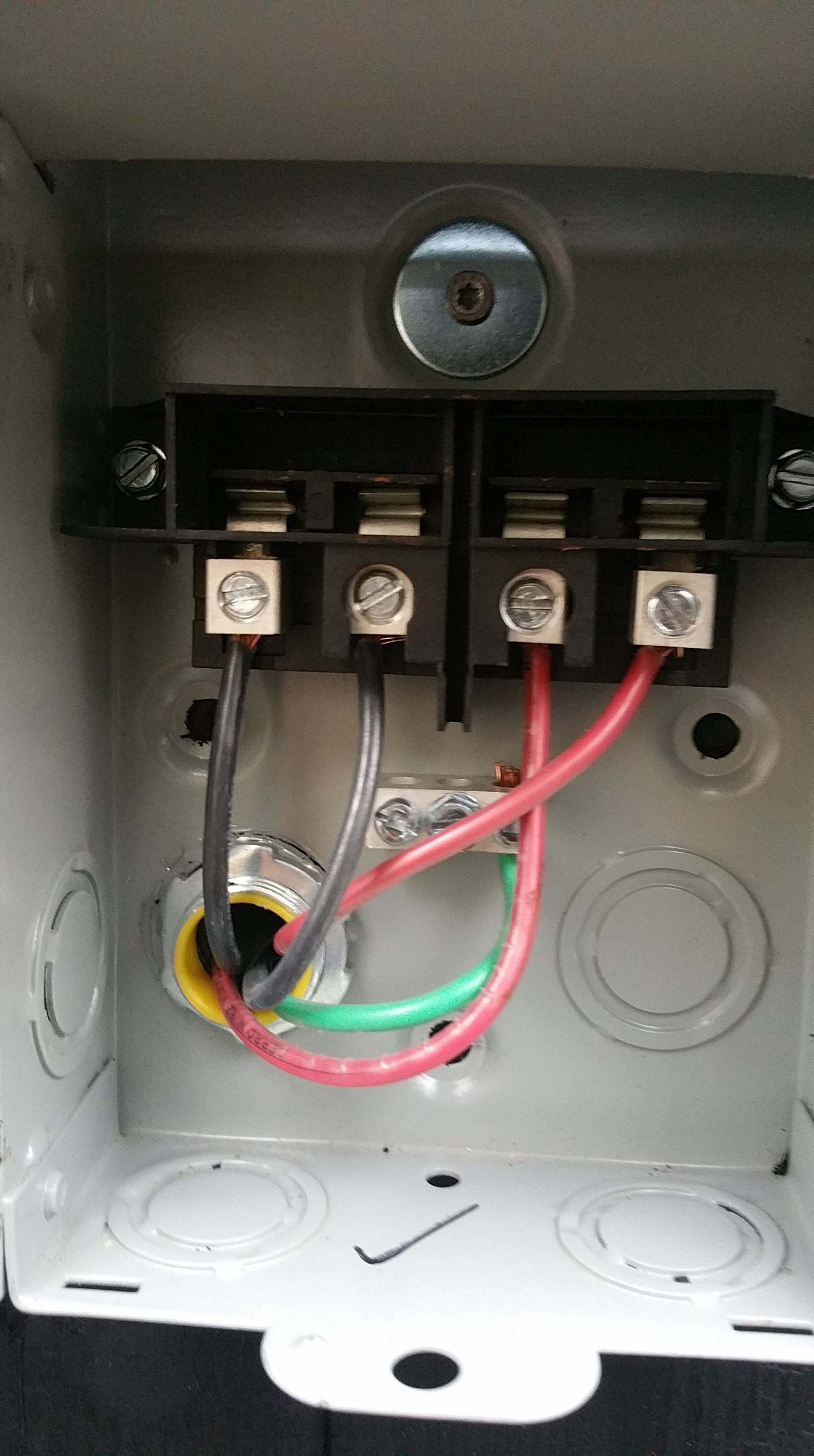

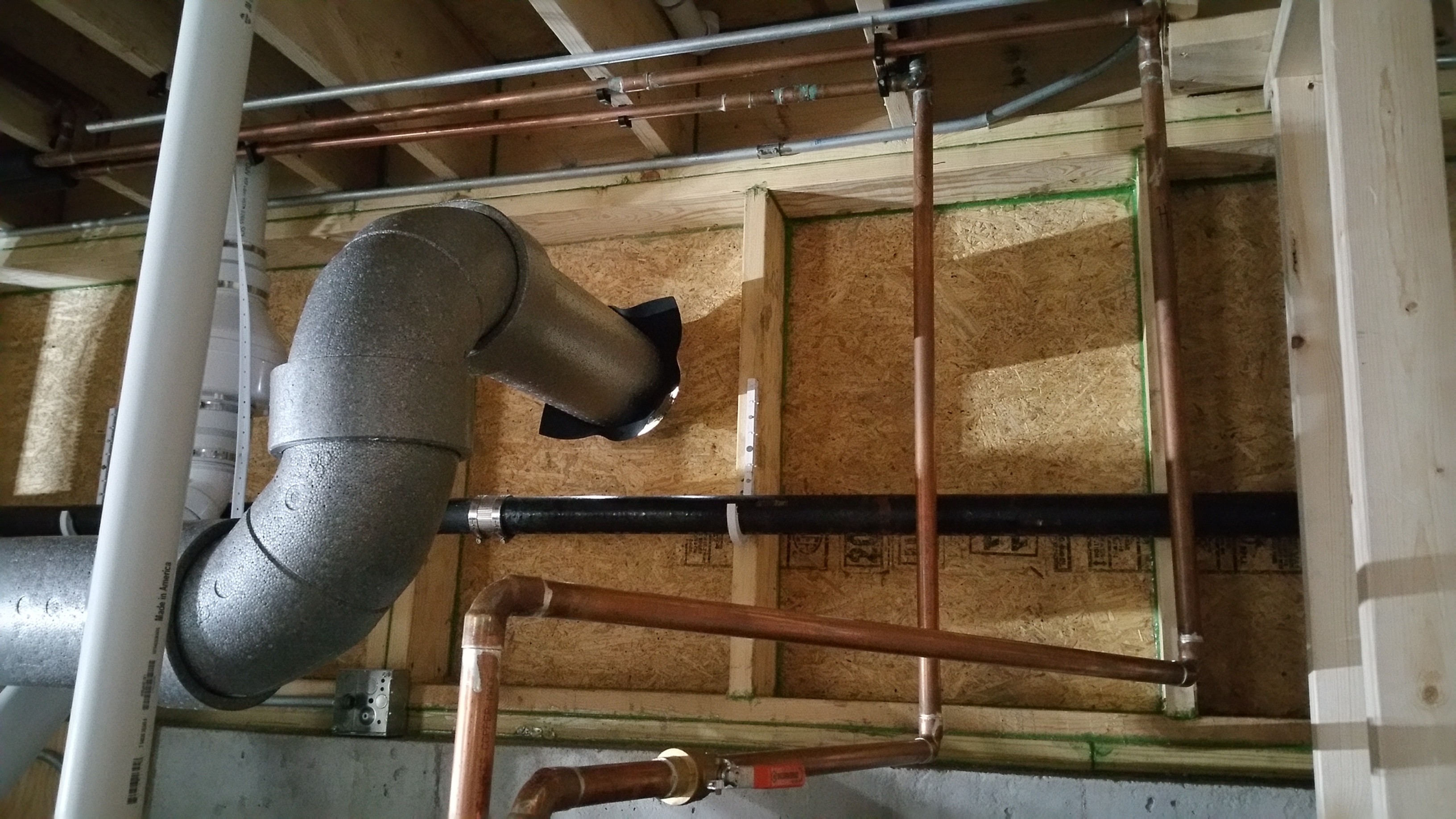

In addition, there is the potential for less upfront expenditures for HVAC equipment (less heating and AC demand — at least in theory — means smaller and more cost-effective equipment is required). In our case, in climate zone 5, where we get cold, dry winters and hot, humid summers, this didn’t prove to be the case. Combining the cost of our heat pump and ERV reflected roughly what we would’ve paid had we built a conventional home with a high efficiency gas furnace with a humidifier attached (fairly typical system in our area). Either way, it would constitute roughly a $20,000 expenditure for a house under 2,000 square feet. The level of indoor comfort, however, should be vastly different between a conventional and a Passive House build.

Even though occupant behavior can derail some of these projected performance outcomes, assuming that homeowners or tenants are reasonably educated on the best way to enjoy and benefit from the Passive House details, especially the HVAC systems (normally this means commissioning units and then mostly leaving them alone in terms of settings), this should not be a stumbling block for most builds.

While all of this becomes more challenging with a smaller, more compact build like our 1,500 square foot single-family home, the possibility of significantly lowering energy demand is no less real, along with the cost savings. Not to mention the level of occupant comfort, which I personally feel is the main selling point of the Passive House building principles.

Some Background Information on Our Home

A quick summary of our build would include our blower door score of 0.2 ACH@50 (106 cfm@50), along with the following R-values for the structure:

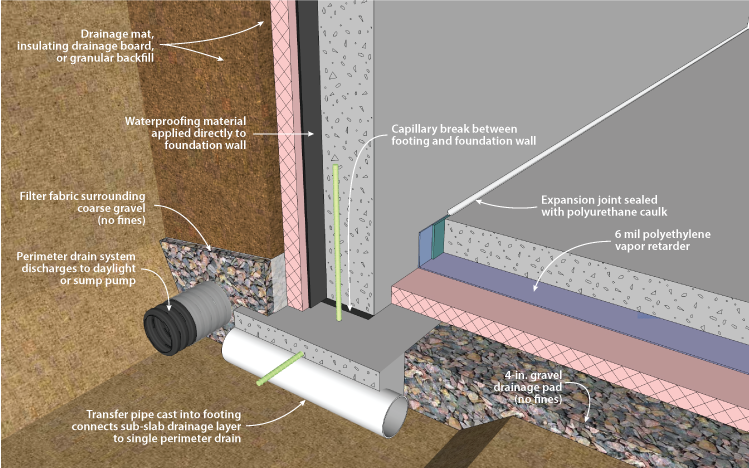

R-16 Below the basement slab

R-20 Exterior of the basement foundation

R-40 Exterior walls

R-80 Attic

In 2019, our first full year of occupancy, with three of us (my wife, daughter, and myself) we had a total of just over 11,000 kWh of energy use. This included lighting, all other plug-in electricity demands (appliances, TV, computers, charging cell phones etc.), along with our HPHW tank and all of our heating and AC needs. It also included countless hours of power tool usage as I finished up interior trim, doors, along with some shelving and storage projects after we moved in. Record low temps during a Polar Vortex event in late January and into early February added to the total as well.

For 2020, a substantial increase in overall energy use might have been the expectation after the outbreak of COVID-19. Yet even after subsequent stay-at-home guidelines that began for us in March, we actually ended up at 10,446 kWh, a slightly lower annual number compared to the previous year. This lower total happened even with all three of us being home most of the time, with no breaks even for vacation time, outdoor activities that require some travel, or normal visits to family out of town.

“If there’s a payoff in pursuing Passive House, it has to be in the combination of lower energy costs and increased occupant comfort when compared to a similar, conventionally built home or structure.”

This lower number was in keeping with our usage during our first nine months (April-December, 2018). If the Polar Vortex was an anomaly (everyone hopes that it was), then most years going forward should be around 9,500-10,500 kWh for total annual energy use. In part we think going over 11,000 kWH our first full year reflects just how significant a colder than normal winter can be on overall energy demand in a Passive House, not to mention heating demand more generally (whether it’s a Passive House or not).

Moreover, for a family of three and a structure of this size with similar performance specs, it seems to suggest that our 3-4,000 kWh of annual usage per person is mostly ‘baked-in’. Meaning, in terms of occupant behavior, there’s not much we could do to further lower these numbers. Perhaps we could take fewer showers, cook less at home (stove and dishwasher), do less laundry, only ‘live’ from dawn to dusk (to avoid using artificial lighting at night), not do any woodworking or other DIY projects (use power tools off site?), and heat the home to only 60º F in the winter and cool to only 85º F in the summer. Obviously, these would be rather extreme measures to chase after the last final few kWh of energy use and, arguably, it wouldn’t be particularly meaningful apart from bragging rights should we end up with a lower annual total.

After all, it’s fair to ask what’s the point of the air sealing, insulation, and triple pane Passive House windows and doors, if it doesn’t produce a much more comfortable day-to-day living experience for those living inside the home or building? If simply chasing energy use were the main objective, reducing it no matter the consequences, then removing all the windows and doors and replacing them with continuous R-40 walls would be a good place to start, but hardly worth considering for obvious reasons. If there’s a payoff in pursuing Passive House, it has to be in the combination of lower energy costs and increased occupant comfort when compared to a similar, conventionally built home or structure.

In terms of unexpected surprises, really the only unanticipated energy use was the need for dehumidification on the hottest and most humid summer days of the year.

After our first summer in 2018, when part of the excess humidity was likely due to new construction moisture present inside the structure, we’ve been averaging about 30-40 days a summer, including a few random days in spring and fall, when the dehumidifiers are running intermittently. We set the units to 50% relative humidity, but normally they shut off around 55% based on gauges placed around the house. We try to keep the house under 60% RH. The risk for mold increases above 60%, but it’s mainly at that point when humidity levels make us feel noticeably uncomfortable.

Also, we didn’t think about the energy use associated with power tools for woodworking and arts and crafts projects. Without tracking it, we can only guess that it represents a few hundred kWh a year, rather than something in the thousands. We’ve been doing plenty of projects around the house our first three years, but still far less than what a full-time woodworking company would require. Even so, along with the potential for a EV charger, it’s something to think about when designing a new home or retrofitting an older one, especially if renewables are part of the equation and you’re trying to establish likely annual demand.

Actual Energy Use: Demand and Costs

The breakdown is as follows:

Based on our first 2.5 years in the house, we can expect 10-11,000 kWh of total energy use per year. Again, for some context, this is for a family of three, in a 1,500 square foot single story home that has a full basement.

In our first full year, 2019, we exceeded 11,000 kWh mainly due to the Polar Vortex. Compared to our first winter, along with numbers for this current season, it looks like the Polar Vortex added nearly 1,000 kWh of demand above a more typical January – March time period.

Over the course of our first 2.5 years (our first year was April-December), the numbers have been surprisingly consistent across seasons and month-to-month, regardless of our level of activity in the home (e.g., guests staying over, vacations away from the home, power tool use, etc.).

For instance, even in our first June, back in 2018, when the house was still drying out from new construction related moisture, and we felt compelled to start using two dehumidifiers to control excessive humidity (one in the kitchen and one in the basement), total energy use for the month was 616 kWh.

The following June, in 2019, we ended up with an even higher number, at 786 kWh of demand.

For June of this year, even with stay-at-home restrictions for COVID-19 in place, so a reasonable expectation might be for still yet higher demand, we actually ended up at a lower 605 kWh of use.

On a side note, it’s probably reasonable to assume COVID-19 had some impact on overall energy use for 2020, but after going through the numbers, it just seems unlikely that it contributed more than 500-1,000 kWh to our annual usage. We should have a better idea of its full impact once winter is over.

Presumably, without a granular study of day-to-day conditions, including day and night temperatures, along with relative humidity data, not to mention minor fluctuations in how we used the AC or how much laundry we were doing over these same three periods, it’s hard to explain this deviation with any level of certainty. Suffice it to say, we can expect June usage to normally be in the 600-800 kWh range. Obviously, a June in the future that experiences a heat wave like the one Chicago experienced in 1995 would likely drive the final number well over 800 kWh, but hopefully that remains a singular event rather than a more normal June.

In other words, even in a year where the weather remains milder than normal for a full 12 months, and we’re all exceedingly busy and rarely at home, our total energy use for the year, at best, will likely still end up in the 9,000-10,000 kWh range. And even if there was just one person living here, it’s hard to imagine they could keep total energy usage much below 4-5,000 kWh on an annual basis since so much of the demand is ‘baked-in’, as previously noted above.

Here is the monthly breakdown of energy use for the first full year we were in the home for 2019:

January: 1,738 kWh (includes 2019 Polar Vortex; following January was only 1,374 kWh)

February: 1483 kWh (the following year was 1,237 kWh)

March: 837 kWh (following year was 561 kWh — clearly a bitterly cold winter)

April: 681 kWh

May: 473 kWh

June: 786 kWh

July: 612 kWh

August: 608 kWh

September: 630 kWh

October: 812 kWh

November: 1,166 kWh

December: 1,237 kWh

Total energy use for 2019 was 11,063 kWh.

In this same period, our solar panels produced 3,863 kWh, so net demand for the year was 7,200 kWh (this requires some math using the billing statements from our utility company and the Enphase Enlighten solar app).

Our monthly bills for electricity in 2019 totaled: $1,075.89.

Because of our SRECs, which for us totaled $848 for the year (paid via quarterly checks), our net energy costs for 2019 were $227.89 (an average of $18.99 per month).

For comparison, numbers for 2020 were: 10,446 kWh of demand, while solar production for the same time period was 3,675 kWh, for a net energy demand of 6,771 kWh.

After SREC payments (again, totaling $848 for the year), our net total cost for 2020 was $189.36 (an average of $15.78 per month).

The SREC payments (these are based on a 5 year contract) reduced our annual cost by $848 each year, with a net average cost for our first two years of just $208.63 per year for all of our energy needs (a roughly $17.39 per month average).

| 2019 Total Energy Use | Solar Production | Net Energy Demand |

|---|---|---|

| 11,063 kWH | (-3,863 kWH) | 7,200 kWh |

| 2019 Energy Costs | SREC’s | Net Energy Costs |

|---|---|---|

| $1,075.89 | (-$848.00) | $227.89 |

| 2020 Total Energy Use | Solar Production | Net Energy Demand |

|---|---|---|

| 10,446 kWh | (-3,675 kWh) | 6,771 kWh |

| 2020 Energy Costs | SREC’s | Net Energy Costs |

|---|---|---|

| $1,037.36 | (-$848.00) | $189.36 |

Without any solar panels or SRECs, our electric bill would be roughly just under $1,500 per year based on current rates. By way of comparison, a new code-built home of the same size would likely pay more than twice this amount — an older home still more, assuming less air tightness and insulation, low quality windows and doors, and with a less efficient gas furnace for HVAC and gas-fueled domestic hot water.

It’s worth noting that as building codes tighten up their performance metrics, the difference in total energy demand between code-built and Passive House homes should continue to shrink. This assumes, however, that any number of ‘ifs’ are successfully overcome. For example, if air leakage is accurately measured (is there enforcement should the structure fail?). If a proper Manual J has been completed. If HVAC ducts are sized, installed, air sealed, and insulated properly. If insulation has been properly installed in appropriate quantities throughout the exterior walls and roof. If thermal bridges are mostly avoided. If moisture (bulk and water vapor) is appropriately addressed and managed. This is a lot to get right, and it’s easy to get any number of things wrong, even with inspections and third party verification.

As pointed out earlier, since we’ve moved in we haven’t aggressively pursued trying to lower our energy demand. Instead, our approach has been to live ‘normally’, enjoying the benefits of the air sealing, insulation, high quality windows and doors, and our high-performance HVAC equipment. We set and mostly forget our heat pump at 70º F in winter, 75º F in summer, in order to try and better understand ‘real world’ energy demand in a tight, well insulated and appropriately ventilated home of similar size.

Hopefully some of this information can benefit others in the planning stages of their own Passive House, or Pretty Good House project. Moreover, in addition to WUFI analysis and PHPP, BEopt is another modeling option for figuring out energy demand and cost-effective design elements for a structure (new or old). The new calculator from PHIUS would also be a good place to start: PHIUS+ 2021

For anyone who wants an easy, initial test of their current home’s energy efficiency (EUI), a calculator like this one may be helpful: Energy Smart

Numbers for Heating and Cooling

In spring and fall when there’s less demand for heating or AC, our baseline monthly energy usage is below 500 kWh (this has been fairly consistent over the course of our 2.5 years in the home, even during COVID-19 when the three of us were home most of the time).

If this low demand could be maintained for much of the year, as it is in milder regions of the country like in parts of California, our annual usage could be cut by more than half (it wouldn’t require R-40 walls or R-80 attics to achieve either). Moreover, in these more temperate regions of the country with reduced insulation needs, and therefore less demand on HVAC systems, ‘green’ building programs like Passive House and Net Zero become even more attractive since they’re far more cost effective and easier to achieve.

In our case, summer months typically run about 600-800 kWh of total usage, dependent on the number of days above 82º F when we typically find that we need to turn on the AC. Even on these days we will turn it off if there’s a sufficient drop in outdoor temps overnight, which allows us to open the windows (dependent on outdoor humidity or rain).

It might be worth noting that even though we thought we’d regularly open our windows whenever the weather was remotely nice, this hasn’t turned out to be the case. Between having to monitor indoor humidity levels, and the ability of our ERV to deliver continuous filtered fresh air (it’s shocking how quickly our fresh air supply filter turns black — within a month or two at the most), apart from the few days a year when the weather is perfect for opening windows, they mostly just stay shut. Much like Jim Gaffigan’s quip on seasons here in the Midwest, “Spring — that’s a fun day,” because the weather tends to be so mercurial there just aren’t that many days or nights when we feel comfortable leaving the windows open for extended periods of time.

On the plus side, it’s not uncommon for us to wait until there are 2-3 successive days where temperatures rise above 82º F before we feel the need to turn on the AC. In other words, there is some truth to the idea that Passive House buildings take some time to heat up or cool down based on outdoor conditions, although this can be quickly undermined by an ERV/HRV that’s set on high or in boost mode for long periods of the day (lots of cooking or showering, particularly relevant in the case of larger families, would make this a necessity) .

“Heating and cooling energy – that which is most reflective of the efforts of the design and construction process – is a small percentage of the total energy usage. As Andy Shapiro says, there is no such thing as a net zero house, only net zero families. Occupant choice matters hugely.”

—Marc Rosenbaum‘s report on South Mountain Company’s Eliakim Net Zero Energy Project

During the heart of winter, our total energy demand is in the range of 1,000-1,500 kWh per month. Even in January of 2019, with a Polar Vortex event, our bill still managed to stay below 2,000 kWh for the month. During this same week, however, we saw minimal benefit from our solar panels since they were covered by several inches of snow during the sunniest (and coldest) parts of the billing period.

These elevated kWh numbers during winter reflect just how much harder our Mitsubishi heat pump system has to work in order to maintain indoor comfort because of the Delta T between outdoor and indoor temperatures. And we can hear the difference: while in summer the system is virtually silent, in winter, especially as temps head towards zero, we can hear the condenser outdoors working to keep up. Compare this to summers: 75º F indoors vs. 95-100º F outside on the hottest days of the year, even though it’s significantly cooler for most of the summer, thus helping to explain the lower overall energy demand for AC usage in comparison to heating demand.

Cooling, unlike the demand for heating, is relatively comparable to what it would be in a conventional new build. In summer the Passive House ‘thermos-like’ structure is mostly a hindrance rather than a benefit to keeping the interior comfortable. All the ‘free’ sources of heat in winter (e.g., south-facing windows on sunny days, body heat from the occupants, heat given off by computers, TVs, appliances, and even LED lights or our heat pump dryer) either thankfully don’t exist (in the case of south-facing glass because of sufficient overhangs) or they actively contribute (however small in some cases) to the overall cooling demand.

In addition, because cooling loads are relatively low, and the efficiency of the mini-split heat pump is so high, even as the multiple indoor wall-mounted units have no issue maintaining comfortable temperatures (we rarely notice the system — wall units or outdoor condenser — running in summer), it leaves us with a latent load that we need to address with two stand-alone dehumidifiers, indirectly adding to the overall cooling load.

| Energy Use by Type: | Total Annual Demand: 9-11,000 (kWh) |

|---|---|

| Heating | ± 3,000 (kWh) |

| Cooling | < 1,000 (kWh) |

| Balance (LED’S, plug-in loads, appliances, HPWH) | ± 5-7,000 (kWh) |

So of our roughly 10-11,000 kWh per year of total demand, without an actual energy use monitor like TED on our main panel to establish exact numbers (a review of current product options: here), it looks like just over 3,000 kWh is used for heating, with another 800-1,000 kWh used for cooling needs (at least in a typical year). In years where there’s a significant Polar Vortex event, or should a summer in the future experience an extended heat wave, then our numbers for heating and cooling are likely to hit 5-6,000 kWh of demand. With climate change, these numbers are invariably going to fluctuate or even grow depending on just how severe weather patterns become over the ensuing years and even decades.

Notes on Designing a Heat Pump System for Passive House

An issue worth considering — especially for those in the design stages of a build — is the added efficiency of a 1:1 set-up for heat pumps, meaning one outdoor condenser for each wall-mounted head indoors (or for each ducted air handler). There appears to be a growing consensus that this layout will offer added efficiency because of improved modulation over what has been a more typical set-up, like ours, which is a multi-zone system that has multiple wall-mounted heads on a single condenser. It’s hard to imagine, at least in our case, that this impact could be more than a few hundred kWh per year, but it’s worth exploring when having someone do a Manual J, S, and D.

Additionally, we haven’t experienced any issues with the distribution heads in the two bedrooms (9k & 6k Btu’s respectively), either for heating or cooling, although concerns about the effectiveness of these lower Btu units in smaller bedrooms often comes up in discussions on how best to design and layout a heat pump system on Green Building Advisor (the concern is that they’re still too large).

When designing our system, I don’t remember this issue of 1:1 vs. multi-zone heat pump set ups being discussed in any of the information I was able to hunt down, either in Passive House-related books, or even in online resources. I also didn’t come across discussion of the need for active, separate dehumidification while designing our build in 2016. These are just two examples demonstrating that Passive House is still actively evolving as a ‘green’ building program (potential overheating in winter and shoulder seasons would be a third example).

A cautionary tale for designers, as well as building owners, to guard against hubris as the construction drawings develop,a or when the details are finally executed on a construction job site. Other issues may arise with Passive House builds in the coming years, so it’s worth considering potential unintended consequences before finalizing details. Today’s solution may be someone’s costly headache tomorrow.

Additional Solar Panels to Achieve Net Zero?

Based on what we’ve been paying for energy in these first 2.5 years, we don’t feel compelled to add more solar panels at this time. Should the SREC’s dramatically fall in value with a new contract, or disappear altogether, it might encourage us, at that point, to purchase more panels for the roof. But even so, at less than $90 per month, even without the SRECs, it makes our energy bills a relatively painless expenditure (roughly equivalent to one nice restaurant dinner for the three of us, or still less than what we pay on a monthly basis for things like coffee, breakfast cereals, and milk). Put another way, averaging around 3,500 kWh per person of demand, whether with or without the solar panels and our SRECs payments, our monthly energy bill is typically cheaper than a single visit to the grocery store.

Because of the effort and money expended upfront for air sealing and insulation, all while trying to carefully manage window placement and HVAC layout successfully, we’ve managed to whittle our energy costs down to something highly affordable and resistant to significant cost increases. This should remain true, regardless of what’s happening in the market in terms of prices for natural gas, coal, or nuclear power (i.e., the major sources of power in our region, here in the Midwest). Worst case scenario, we add additional solar panels to get to Net Zero or even Net Positive in order to cancel out what remains of our monthly energy bill. This would require an additional 7-8,000 kWh of annual solar production, or roughly 2.5-3 times what our current, relatively small, system produces.

In our specific case as a household — averaging between 3,500-4,000 kWh of solar production per year (this amounts to nearly 40% of our annual demand), combined with SRECs — we nearly end up at Net Zero, at least in terms of total cash spent for energy (arguably the most important — maybe the only — metric that homeowners ultimately care about; whether it’s the total cost to build a new home, or in terms of the annual energy bill). As a result, there’s not much financial incentive to purchase additional solar panels to achieve absolute zero energy consumption (this is in site energy terms only). The fact that this all comes with a house that’s extremely comfortable and quiet to live in, regardless of the season or the room, makes our home only that much more valuable to us.

Passive House + Net Zero?

In addition to designing for Passive House, there is the question of Net Zero or even Net Positive buildings. While Passive House strategies eliminate a significant portion of overall demand by requiring a significant outlay of upfront funds for air sealing and insulation, once this pill has been swallowed, it’s normally cost-effective to incorporate renewable energy of some kind to cancel out the expense of the remaining energy bill.

A quick side note: An excellent resource, one that I found only as our build was coming to an end, is William Maclay’s book The New Net Zero. It contains a wealth of information, but, in particular, many specific construction details vividly illustrated. This is especially valuable for DIY builders, or even seasoned professionals, when evaluating all the possible elements of roof-wall-foundation assemblies.

Also worth noting, if this approach (Passive House + Net Zero) were adopted on a national level, including renovations, it would eliminate a large portion of aggregate energy demand, thus having a meaningful impact on greenhouse gas emissions and global climate change (up to 40% for construction and existing buildings).

Based on what we know at the moment, a combination of approaches — including Passive House building principles, Zero Carbon goals, and the use of renewables — could be the way out of the climate crisis over the long haul. In addition, if adopted as part of building codes, it could mean properly training the next generation of tradespeople (like European-style apprenticeship models, thereby also improving the build quality) while also being a tremendously effective jobs program.

Beyond Net Zero, or even Net Positive, in regards to energy demand, there is increasing awareness about carbon emissions more generally, and the variety of ways to radically reduce or sequester it, including the choice of building materials (for new construction or retrofit projects) or even how we decide to landscape our yards.

Passive House Cost Premium

Unfortunately, due to relatively inexpensive utility rates here in the Midwest, even though Passive House (or Pretty Good House) offers a significant reduction in energy costs if done well, when considered as a percentage of household income the numbers may appear much less impactful or motivating when faced with line items in a build budget for things like air sealing and levels of insulation that far exceed building code requirements.

In our case, the annual energy savings compared to something code-built would likely be in the $2-3,000 range. Fairly significant, but if the purchase price of the home is $500,000 – 1,000,000+ (fairly typical here in the Chicago suburbs for new construction) then even a $100,000 savings over the course of a 30 year mortgage may not convince someone to move beyond conventional construction practices (particularly if they have their heart set on a long list of high-end finishes and appliances). The upfront costs associated with meticulous air sealing and added levels of insulation — if not viewed as an investment in build quality — will likely appear frivolous to the average consumer.

“One of the issues we face here is the fact that energy is cheap, like most things in the Midwest. We don’t have the financial burden placed on us that the coasts do—real estate-wise and energy-wise. So there is not much enthusiasm around green building on a financial level; it’s almost always an ethical issue. The people who are interested want to do a good thing for the environment, as opposed to saving money on their utility bills. Another thing is that people are accustomed to discomfort—we have drastic and frequent temperature swings. It’s really humid in the summer and freezing in the winters, when drafty windows are just accepted. They are used [to] it, so it is hard to sell them on high-performance windows to be more comfortable; or taking measures to keep a basement from being wet—they just aren’t concerned about it. There’s a complacency that we fight against; there’s not enough financial gain to incentivize making upgrades.”

— Travis Brungardt, GBA Q&A

Looking solely at upfront costs is likely to discourage most prospective homebuyers from pursuing Passive House (or even Pretty Good House in many cases), whereas looking at the cost of ownership, including the cost of monthly utilities, produces a more accurate comparison (note, however, this assumes the homeowner can stay put for at least the next twenty to thirty years).

A cost of ownership calculation should also acknowledge less maintenance costs year-to-year since, if the structure is detailed well, it should experience far fewer issues (none ideally), especially damage caused by bulk water intrusion, mold, or even air leakage. Granted, it may take a decade or more before this kind of damage is found in a conventional home, but when it is, it’s rarely (if ever) inexpensive to properly correct.

Hard Choices

As a culture, we have been in a similar place before. One quick example would be automotive engineering applied to car safety. In terms of perspective, if you get the balance between cost and safety wrong when evaluating value, then seat belts, air bags, and better designed bumpers might seem like misspent dollars.

“Nader argued that Detroit willfully neglected advances in auto safety, like roll bars and seat belts, to keep costs down… But using [seatbelts] was strictly voluntary. And many Americans didn’t want to.”

— Daniel Ackerman, ‘Before Facemasks, Americans Went to War over Seat Belts’

In a similar vein, the American consumer has been taught by the market, realtors, and builders to believe cost per square foot is the gold standard of value. As a consequence, little emphasis is placed on building science basics such as air tightness, proper moisture management, thermal performance, or indoor air quality. In layman’s terms, this means the average American home is leaky, parts of it have likely been damaged by bulk water or mold, and it’s uncomfortable in terms of indoor temperatures and humidity, all while delivering subpar air quality to its occupants.

In terms of quality construction and ‘green’ building (Passive House or not), the hard truth is there really is no free lunch (not even renting: rentcafe). Quality, of any kind — finishes, proper moisture management, occupant comfort, even reduced energy bills — has its price, but only those who recognize its value will be willing to pay for it.

Regardless, as homeowners we either pay upfront for the air sealing and insulation, along with high performance HVAC for better IAQ, or we pay monthly (and perpetually) in the form of higher energy bills (this normally comes with less occupant comfort) and far inferior IAQ. Either way, the money is going to be spent, it’s just a question of when (upfront vs. long term month-to-month) and for what (air sealing and insulation vs. mediocre systems and underwhelming outcomes that require costly maintenance over time).

As with car safety in the past, depending on one’s point of view, the answer to these kinds of construction and homeownership options are either obvious or nonsensical. Nevertheless, regardless of the path taken — conventional construction or some version of high performance — no one’s wallet will remain closed for long.

You must be logged in to post a comment.